What Is a Pulmonary Embolism?

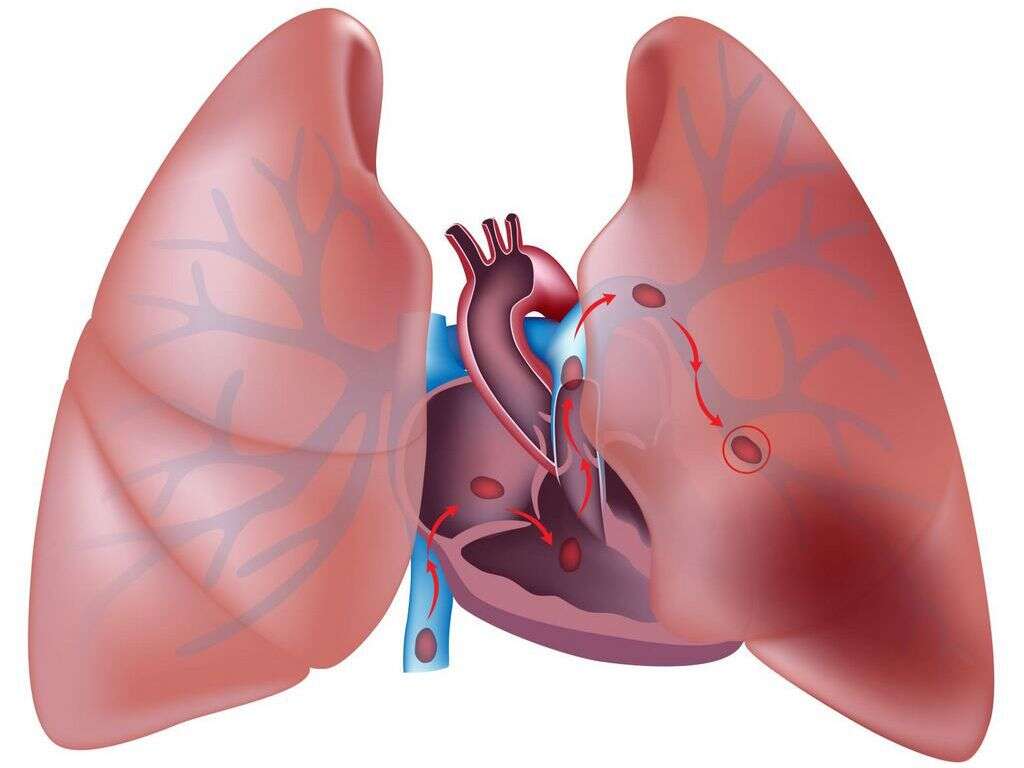

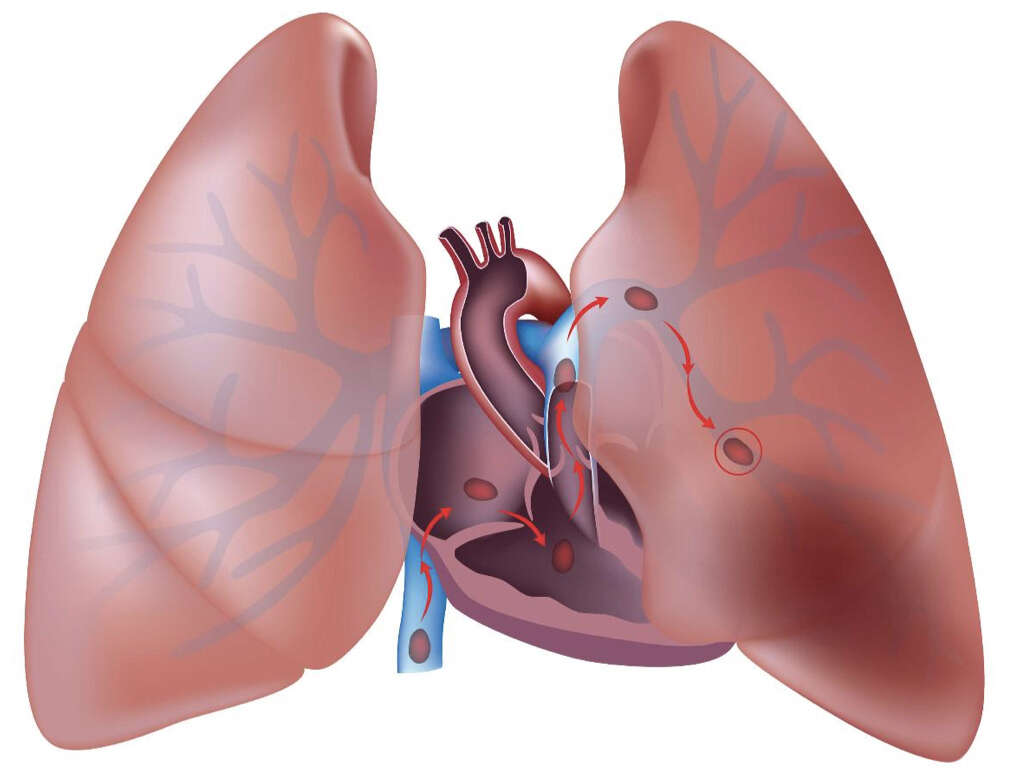

Pulmonary embolism occurs when a blood clot becomes lodged or stuck in an artery in the lung. This blocks the blood flow to the lung and causes various issues. Pulmonary embolism usually occurs due to a thrombus that has travelled from other parts of the body. The clot is most likely from the deep venous system of the lower limbs. However, it can also originate from the veins of the upper extremities, renal, pelvic, or the heart.

When the thrombus (blood clot) travels to the lung, a large clot can lodge itself at the bifurcation of the lobar branches or main pulmonary artery resulting in various symptoms. It is important to realize that pulmonary embolism is not a disease itself but is a complication due to venous thrombosis. Normally, small clots are continuously formed and lysed in the venous system.

1. Etiology

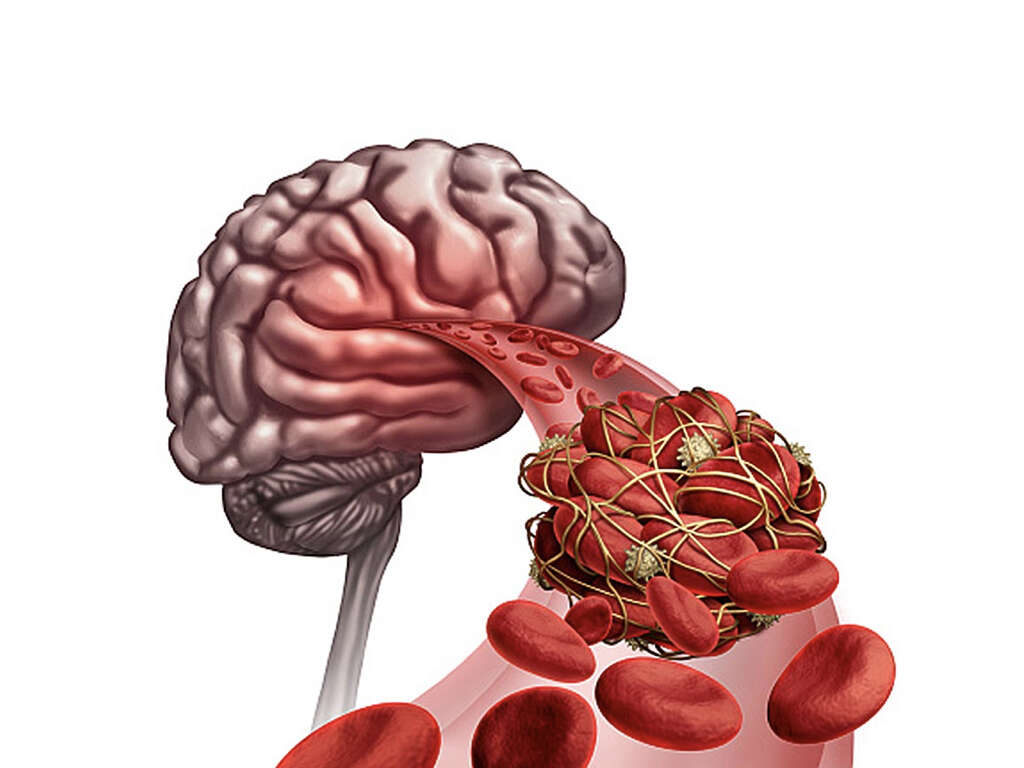

There are 3 main factors that predispose the formation of a blood clot: endothelial injury, blood flow turbulence or stasis, and hypercoagulability of the blood. A venous thrombus can grow in size due to the accretion of fibrin and platelets. This may either result in blockage of the vein or it may break off and embolize.

Due to the venous return, large clots can lodge at the lobar branches or bifurcation of the main pulmonary artery while smaller clots travel more distally to block smaller vessels located in the periphery of the lungs. Any condition or medication that increases the coagulability of the blood increases the risk of pulmonary embolism.

2. Risk Factors

Various conditions and medications can increase the coagulability of blood. For example, some of the following are risk factors for pulmonary embolism: pregnancy, oral contraceptives, estrogen replacement therapy, malignancy, hereditary factors, and obesity.

Any condition where there is venous stasis also increases the risk of pulmonary embolism as it leads to the accumulation of thrombin and platelets in the veins. This includes immobilization, surgery, and trauma. Among patients found with clots in their veins, as many as 17% were found to have an underlying malignancy. Pulmonary embolism has been reported in patients with lymphomas, leukemias, pancreatic carcinoma, genitourinary tract carcinoma, colon cancer, and breast cancer.

3. Pulmonary Embolism in Children

Compared to adults, almost all (98%) children with pulmonary embolism have been found to have a serious underlying disorder or identifiable risk factor. This includes an indwelling central venous catheter (21%), central lines (36%), hereditary disorders of coagulation (protein C deficiency, protein S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency), and abnormalities with their antiphospholipid antibodies.

Another study reported that pulmonary embolism was present in more than 33% of children who have been treated with long-term hyperalimentation (feeding of nutritional products intravenously). The very same study also reported that in 30% of these children, pulmonary embolism was the main cause of death.

4. Epidemiology

In the United States, the incidence of pulmonary embolism is estimated to be 1 per 1,000 people annually. A study from 2008 has suggested that the use of computed tomography has led to increased reports of the condition.

It has been estimated that pulmonary embolism occurs in 60% to 80% of patients with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) despite more than 50% being asymptomatic. It is the third most common cause of death among hospitalized patients. Autopsies have found that pulmonary embolism was present in about 60% of patients who died in the hospital with the diagnosis missed in 70% of the cases. Internationally, the incidence is most likely due to the accuracy of diagnosis.

5. Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms in pulmonary embolism include breathlessness, rapid breathing, cough, chest pain worsened by breathing, and cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the lips and fingers). It can also cause syncope and sudden death.

A low-grade fever may also be present. However, patients rarely present with the classical presentation of pulmonary embolism. In a study of patients who have died unexpectedly due to pulmonary embolism, 40% of the patients have previously been seen by a medical professional weeks before their death due to nagging symptoms. In the patient’s history, it is important to try to establish if there are any conditions or medications that causes a hypercoagulable state. Other risk factors to look for include history of recent surgery, malignancy, history of travel, trauma, and smoking.

6. Approach to Diagnosis

Since the signs and symptoms for pulmonary embolism are nonspecific, those suspected of a pulmonary embolism should undergo diagnostic tests until the diagnosis is achieved, eliminated, or an alternate diagnosis confirmed.

Routine laboratory tests are also nonspecific and are generally not helpful in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Screening for conditions such as protein S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency, protein C deficiency, homocystinuria, occult neoplasm, lupus anticoagulant, and connective tissue disorders should also be considered if there is no obvious cause for the embolism. When there is a low to moderate pretest probability, a D-dimer test may be performed. A negative result indicates a low likelihood of thromboembolism and the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism may be excluded.

7. Investigations and Prevention

Some of the tests and imaging that can be performed include ischemia modified albumin levels, arterial blood gases, white blood cell count, troponin levels, venography, angiography, brain natriuretic peptide, chest radiography, computed tomography (CT), ventilation perfusion scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electrocardiography, echocardiography, and duplex ultrasonography.

When patients with risk factors are admitted, they can receive medication that reduces the likelihood of pulmonary embolism such as low molecular weight heparin, unfractionated heparin, and anti-thrombosis stockings. Long-term aspirin also helps to prevent the recurrence of pulmonary embolism.

8. Approach to Treatment

Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis can still occur in patients who receive anticoagulants. In children, the treatment of choice is anticoagulants. There is very little evidence regarding the use of low molecular weight heparin in children who have thromboembolic disease. In adults, anticoagulants are the mainstay of treatment.

In acute cases, supportive treatments such as analgesia and oxygen can also be important. Patients given warfarin may remain in the hospital until they reach therapeutic levels. Low-risk cases can be managed at home. Thrombolysis can be used in patients who have acute pulmonary embolism, hypotension, and low risk of bleeding. Thrombolysis in this group should not be delayed as it can result in irreversible cardiogenic shock. Other treatment options include embolectomy and the insertion of a vena cava filter.

9. Supportive Care and Monitoring

The use of elastic compression stockings is a safe and effective treatment for those with proximal deep vein thrombosis. Activity such as early ambulation is recommended. Dopamine and dobutamine are inotropic agents that can support the cardiovascular system if necessary.

Intravenous fluids may benefit the patient who is hypotensive depending on the patient’s condition. Long-term anticoagulants are crucial for those with a history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. In pregnancy, fibrinolysis and heparin use are safe. These patients can be treated with low molecular weight heparin throughout their pregnancy. Consultation with a pulmonologist, cardiologist, and hematologist can also be beneficial.

10. Prognosis

The prognosis of patients with pulmonary embolism depends on 2 factors: appropriate diagnosis and treatment along with the underlying disease state. It is estimated that about 10% die within the first hour while an additional 30% die from recurrent embolism.

With the use of anticoagulants, the mortality decreases to less than 5%. In undiagnosed pulmonary embolism, the mortality is 30%. A study showed that the mortality rate at 1 year was 24% due to recurrent pulmonary embolism, cancer, infection, and cardiac disease. With a massive pulmonary embolism, the mortality ranges from 30% to 50%. Studies have shown that 80% of patients who died unexpectedly in the hospital had a pulmonary embolism. Estimations show that about 95% to 96% of patients experience a nonmassive pulmonary embolism.