What Is Osteopenia?

The World Health Organization coined the term osteopenia in 1992 to describe a previously unnamed condition. It refers to a loss of bone mineral density that causes problems for the patient, but that is not quite serious enough to be classified as osteoporosis.

People with osteopenia have a high risk of broken bones. The condition can be thought of as a precursor to osteoporosis, because people with osteopenia are likely to eventually develop the disease. Here are answers to ten frequently asked questions asked about this condition that affects millions of Americans.

1. What Are the Symptoms of Osteopenia?

Often the first clue that a person suffers from osteopenia is a broken bone in the wrist, hip, or vertebral column. Before this fracture occurs, there is usually no pain and no other symptoms. People are sometimes unaware that a bone has even broken, because their bones have weakened to the point that they break easily, with little or no pain. After a break, bones usually feel weak and sore.

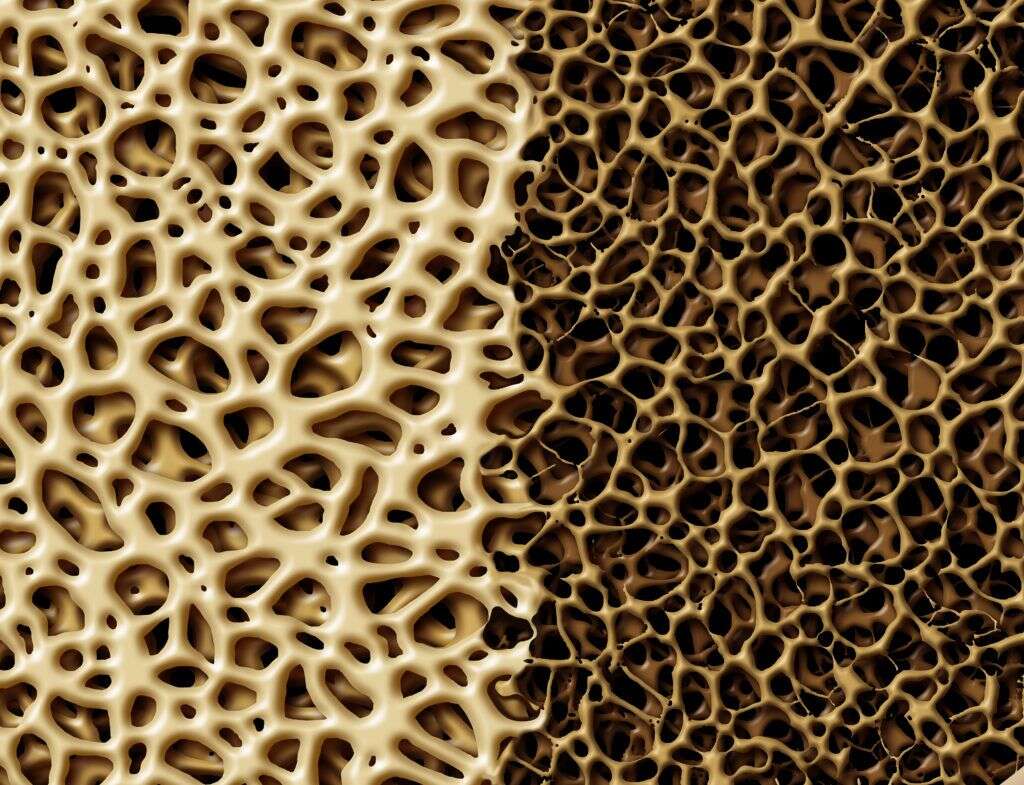

If people could see their bones at the microscopic level, the warning signs of osteopenia would be hard to miss. The word osteopenia comes from two words meaning “bone” and “poverty,” a name that does a good job describing the condition. Bones with osteopenia are impoverished in the sense that they are lacking the density present in healthy bones. Under a microscope, you would be able to see pores among the normal honeycomb-shaped structures. These pores become more pronounced as the disease progresses.

2. How Does Osteopenia Differ From Osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is a serious medical condition in which bones have lost so much mass that they are brittle and break easily. Broken bones are sometimes also the first sign of osteoporosis, but other warning signs are back pain, loss in height, or a curving upper spine.

Osteoporosis means “porous bone,” referring to the spaces, or pores, that form inside as osteopenia becomes more advanced. Breaks can occur after falling, bumping into furniture, or sometimes even sneezing or coughing. Although osteopenia does not always develop into osteoporosis, it can be thought of as the early stages of it.

3. How Does Osteopenia Differ From Osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is a condition that occurs when the cartilage at the ends of the bones wears away. It is known by many other names, including joint degeneration, joint narrowing, or bone spurs. When the condition affects the vertebral column, it is also called degenerative disc disease or spinal stenosis.

Osteoarthritis is similar to osteopenia in that it involves the loss of tissue, and many people suffer from both conditions simultaneously. Cartilage is a different type of tissue than bone, and it is lost primarily due to a slow grinding down over the years. Osteoarthritis causes pain, swelling and stiffness in the hands, knees, spine, and hips, among other places. Without cushioning between bones, some people also feel or hear bones scraping together when they move.

4. What Causes Osteopenia?

Babies and children build bones faster than they are broken down, causing them to grow in length and the child to get taller. A young person stops growing taller in their early twenties, and by age 35, most people have stopped gaining bone mass. As people continue to age, the process of losing bone mass starts to happen faster than that of replacement. After menopause, the lack of estrogen women experience further exacerbates bone loss. However, not everyone over 50 loses enough bone mass to cause osteopenia.

In addition to age-related bone density issues, the continued use of some prescription drugs has been shown to contribute significantly to bone loss. The medications implicated include antacids and acid reflux medications, anti-seizure medications, chemotherapy drugs, blood thinner, and thyroid hormones, among others. Ask your doctor or pharmacist if your medications put you at risk for losing bone mass.

5. Who Is at Greatest Risk for Osteopenia?

Millions of new cases of osteopenia are diagnosed each year, and one medical institution estimates that up to 50 percent of all people in the United States over 50 years old have osteopenia. Those at greatest risk are Asian and Caucasian people, especially women over age 50. All genders are races are susceptible, however, especially those with a family history of bone loss.

A primary lifestyle choice that increases risk is lack of regular, weight-bearing exercise. Excessive exercise can be just as dangerous if it leads to being severely underweight or malnourished. People who drink alcohol or smoke tobacco, who are deficient in vitamin D and calcium, and who suffer from celiac disease also are at increased risk.

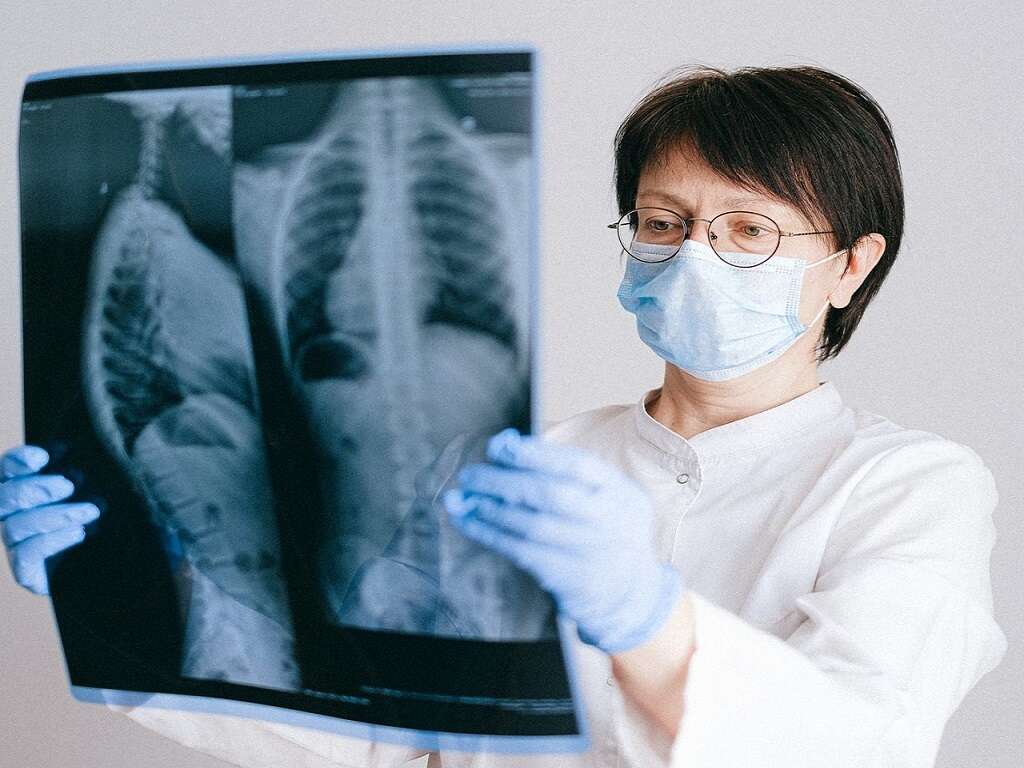

6. How Is Osteopenia Diagnosed?

If a doctor suspects osteopenia, he or she may order a dual-energy X-ray absorption (DEXA) test of the lumbar vertebrae, femur, and radius. This quick and painless diagnostic scan compares the density of the bones to those of a 30-year old person of the same sex. The result is called a “T score.” A score of -1.0 to -2.5 indicates osteopenia, and less than -2.5 osteoporosis. Alternatively, the patient’s bone density can be compared to that of a healthy person of the same age and sex, and the result reported as a “Z score.” A Z-score above -2.0 is considered normal.

The DEXA test is not recommended for patients with scoliosis, degenerative vertebral disorders, calcium deposits in the aorta, or irregular body size (obese, very small, or very tall). In these cases, a quantitative computed tomography of the spine is used instead. This test measures bone mineral density, primarily of the lumbar vertebrae and hips, by creating either a two-dimensional or three-dimensional image that compares the bones to a reference material.

7. Is Osteopenia Considered a Disability?

People with osteopenia must live with an increased risk of fracturing a bone. Many individuals continue to work and live active lifestyles and do not consider themselves disabled. However, this is a highly personal point of view that depends on factors like a person’s other medical conditions, work situation, and general outlook on life.

Whether or not osteopenia could legally be considered a disability depends on many variables and would be decided on a case-by-case basis. Criteria considered might include age and whether the condition prevents a person from doing the type of work he or she has always done. The Social Security Administration publishes what is known as a Blue Book, which lists and classifies qualifying disabilities. There is not a section for either osteopenia or osteoporosis in this publication, although there is one for broken bones.

8. What Medications Are Used To Treat Osteopenia?

When deemed necessary, bisphosphonate medications are prescribed to slow the rate of bone loss. They are taken anywhere from once per day to once per year and have side effects of nausea, dizziness and sometimes fever. Long-term use can also cause osteonecrosis of the jaw and increase the chance of a break in the femur. Examples of these medications are alendronate (Binosto and Fosamax), ibandronate (Boniva), risedronate (Actonel and Atelvia), and zoledronic acid (Reclast and Zometa). Other prescription medications include Denosumab or hormone therapy to increase estrogen or thyroid hormones.

Osteopenia does not always warrant drug treatment. Medications have potential side effects, including cancer and cardiovascular disease, which must be weighed against their benefits. Doctors decide whether to prescribe medication based on the age of the patient, the degree of bone loss and the probability of fracturing a hip. The risk of hip fracture is used as a criterion due to the low survival rate of elderly patients after this type of injury.

9. How Can Individuals Prevent Osteopenia?

Young people can prevent osteopenia by gaining as much bone mass as possible before they reach age 35. Even though they may not be gaining mass, people older than 35 can still make lifestyle choices to prevent or slow down age-related bone loss. The most important activity is to do weight-bearing exercise on a regular basis and to maintain an optimal weight for a person’s age and height.

Diet also plays a role in preventing bone loss. People should eat calcium- and nutrient-rich foods and consider supplementing with vitamin D. Medications with known detrimental effects on bone density should be avoided if possible, and hormone therapy should be considered for post-menopausal women.

10. What Exercises Can Help Increase Bone Density?

A weight-bearing exercise is any activity in which the bones must carry some sort of weight. This does not mean individuals must lift weights in the traditional sense, because a person’s bodyweight alone is enough to strengthen bone tissue. Walking, running, tennis, and calisthenics are all weight-bearing exercises; activities like bicycling or swimming, on the other hand, are not.

Studies have shown that as little as 12 to 20 minutes of this type of exercise done three times per week is enough to have a positive effect on the bones. Surprisingly, one study found that the best exercise was jumping 20 times per day. Other top-rated exercises to improve bone density include stair running, hiking, backpacking, and aerobics.