What Is Barrett's Esophagus?

A change in the normal or physiologic “stress” on an organ leads to an adaptive change in the type of cells that make up its lining. This change in cell type is called metaplasia, and it commonly involves a change of one type of surface epithelium to another that is better able to handle the new stress.

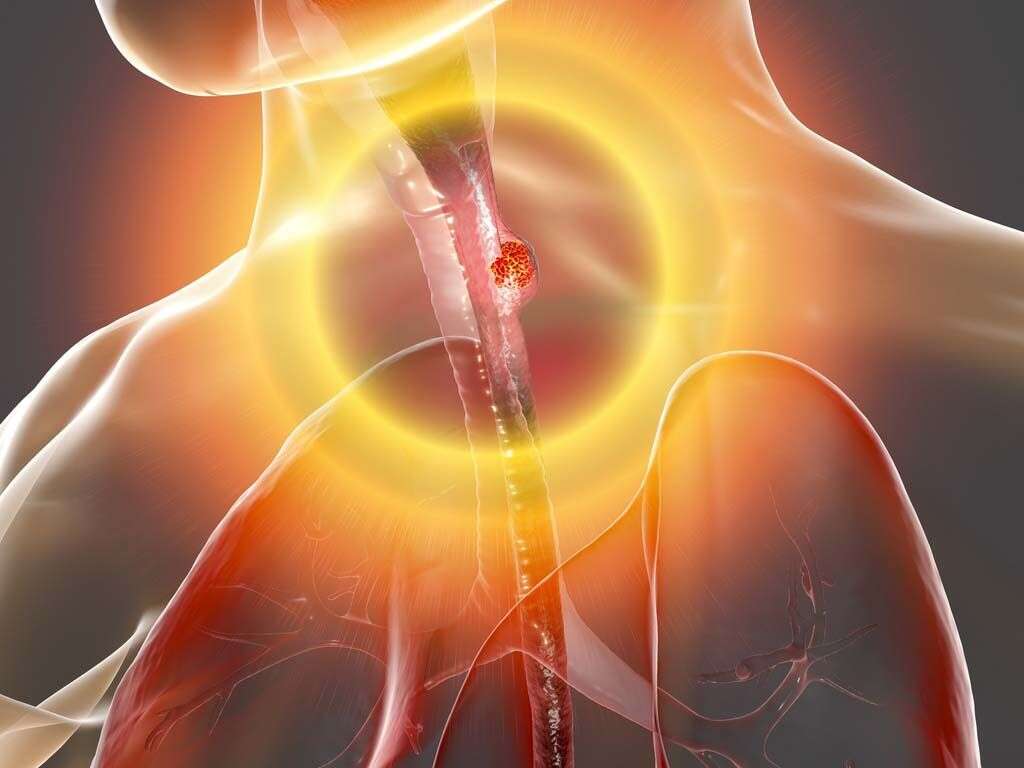

Barrett’s esophagus is a condition that affects the lining of the lower esophagus, the part of the gastrointestinal tract that connects the throat to the stomach. It is a well-known complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which is a chronic condition that occurs when stomach acid frequently flows back into the esophagus. When the lining in the esophagus is exposed for a prolonged duration to the reflux contents, it can lead to erosion and inflammation of the esophageal mucosa. This damage leads to metaplasia or the replacement of the esophageal lining or stratified squamous epithelium (better suited to handle friction of the food bolus) with one that resembles the stomach’s and is better able to handle the stress of acid (mucin-producing columnar epithelium). This transition is considered to be a premalignant change, which means that under persistent stress it can progress to dysplasia and eventually result in esophageal cancer (adenocarcinoma of the esophagus). In theory, with the removal of the driving stressor (treatment of GERD), metaplasia (Barrett’s esophagus) is reversible.

1. History

Barrett’s esophagus is named after Australian thoracic surgeon Norman Barrett. The definition of this condition has evolved over the last century. In 1906, it was described by a pathologist as peptic ulcer of the esophagus. Over the next four decades, the debate revolved on the anatomic origin of the mucosal anomaly. In 1950, Barrett supported the ideology that the stomach was tethered within the chest due to a congenitally short esophagus. However, in 1953, it was argued by Allison and Johnstone to be esophageal tissue and was agreed by Barrett in 1957. The histologic description for the next two decades vary and by 1976, a report on the histologic spectrum of the condition was published where biopsies were performed using manometric guidance.

2. Epidemiology

Barrett’s esophagus most commonly occurs in patients aged 55 to 65 years old. It occurs more commonly among males compared to females with Caucasian males making up more than 80% of cases. There are also some studies that show that there is a higher prevalence of the disease among those with obesity, alcohol intake, and smoking.

The prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus varies and ranges from 0.9% to 10% of the general adult population.

3. Etiology

As mentioned, this condition is a well-known complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease. However, patients with GERD who develop this condition usually have a combination of several factors such as a reduced lower esophageal sphincter pressure, hiatal hernia (a condition where part of the stomach pushes up through the diaphragm muscle into your chest), reflux from the duodenum to the stomach, and delayed esophageal acid clearance time.

Abdominal obesity is also a risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus. In normal cases, the esophagus has several defense mechanisms against the reflux contents such as epithelial defense factors and an antireflux barrier (high pressure zone at the junction of the esophagus and the stomach). Other defense mechanisms include gravity, peristalsis (wave-like contractions that move content through the gastrointestinal tract), and bicarbonate secretion from the esophageal and salivary glands.

4. Patient History and Physical Examination

The classic patient history of an individual with Barrett’s esophagus would be a middle-aged white man who has little to no symptoms. In most cases, there can be a chronic history of gastroesophageal reflux disease, which may or may not include dysphagia (difficulty swallowing). Very rarely, patients may recall previous episodes of hematemesis (vomiting blood).

Other symptoms such as pain under the sternum (this is generally the location where the esophagus meets the stomach) and unintentional weight loss due to painful eating (odynophagia) may also be present. Patients with Barrett’s esophagus tend to have central obesity.

5. Workup

Since there is an important association between GERD, Barrett’s esophagus, and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, patients with a history of chronic GERD, who are 50 years or older, should have an upper endoscopy performed to screen for Barrett’s esophagus. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the preferred procedure to diagnose Barrett’s esophagus.

However, a biopsy will be needed to confirm the findings of specialized intestinal metaplasia (SIM). When cancer or dysplasia is found, an endoscopic ultrasonography is required to evaluate the resectability (ability to be removed by surgical procedures).

6. Approach to Treatment

There is no specific therapy for Barrett’s esophagus as there is little evidence that supports that anti-reflux or anti-secretory agents lead to regression of Barrett’s esophagus or prevents the occurrence of adenocarcinoma.

Currently, the aim is to control the symptoms and encourage healing of the esophageal mucosa by treating GERD. Since medications can only help reduce the acid, surgical therapy may also be beneficial in controlling reflux symptoms. Once high grade dysplasia is discovered, ablation (surgical removal) is the standard of care. The dietary recommendations for patients with Barrett’s esophagus is the same for those with reflux.

7. Screening

The American College of Gastroenterology recommends that individuals experiencing chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease for more than 5 years, especially those ages 50 and above, should have an upper endoscopy performed to screen for Barrett’s esophagus.

If positive, these patients should be monitored to identify the histologic markers for dysplasia or cancer. The goal of surveillance or repeated endoscopy is to detect early cancer or dysplasia.

8. Management of High Grade Dysplasia and Ablative Therapy

The management of high grade dysplasia is controversial. The first step would be confirmation of the diagnosis by a certified pathologist who specializes at reading esophageal biopsies. Based on available literature, it is estimated that as many as 40% of patients who undergo esophagectomy (surgical removal of part of the esophagus) for high grade dysplasia were found to have concomitant cancer in the specimen that was resected.

There are three management options for high grade dysplasia: surveillance endoscopy with intensive biopsy, endoscopic ablation, or surgical resection. In ablative therapy, the goal is to destroy the Barrett’s epithelium to eliminate intestinal metaplasia and promote regrowth of squamous epithelium. Some options include radiofrequency ablation, photodynamic therapy, argon plasma coagulation, multipolar electrocoagulation, laser ablation, and cryoablation.

9. Medication

The medication used for patients with Barrett’s esophagus would be the same for patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. However, most experts agree that a proton pump inhibitor should be used instead of an H2 receptor antagonist because of the acid insensitivity in those with Barrett’s esophagus.

The evidence remains inconclusive. Some examples of H2 receptor antagonists are ranitidine, famotidine, nizatidine, and cimetidine. Proton pump inhibitors include omeprazole, lansoprazole, esomeprazole, dexlansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole sodium. Remember that you must always consult with a medical professional for adequate treatment.

10. Prognosis

The morbidity rate is significant when the condition leads to the development of adenocarcinoma in the esophagus. Although most patients with Barrett’s esophagus do not progress to develop esophageal cancer, the risk of progressions is about 0.5% per year in those without dysplasia.

However, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rapidly rising. For example, from 1926 to 1976, only about 0.8% to 3.7% of esophageal cancers were reported to be adenocarcinomas. This increased rapidly to 54% to 68% from 1979 to 1992. Patients with long segment Barrett’s esophagus have the highest risk for dysplasia and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.