What Causes Prostate Cancer?

Prostate cancer originates from the prostate, a gland found in the male reproductive system. Although generally a slow growing caner, thousands die every year. It is also the second commonest cause of cancer death in males. In cases where growth is rapid, the cancer cells may spread to other areas of the body, especially the lymph nodes and bones.

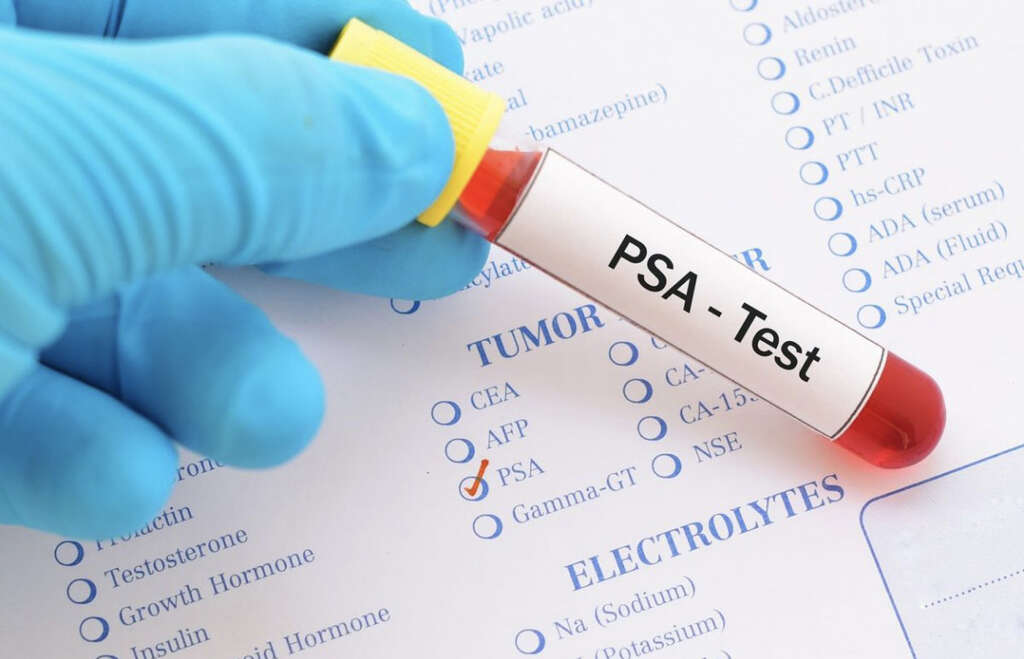

The variation in prostate cancer rates among different populations have suggested the involvement of genetic factors. Currently, most prostate cancers are diagnosed in asymptomatic patients using the prostate specific antigen (PSA) level test or findings via a digital rectal examination. Public education is important as it helps men to make a decision regarding screening using the PSA test and treatment choices for those diagnosed with prostate cancer.

1. Pathophysiology

Prostate cancer occurs when there is excessive cell division, resulting in uncontrolled tumor growth. As many as 95% of prostate cancers are adenocarcinomas. About 4% of prostate cancer is thought to originate from the urothelial lining of the prostatic urethra. Mutations of genes such as those for p53 and retinoblastoma may cause tumor progression and metastasis. In prostate cancer, 70% occur in the peripheral zone, 15% to 20% in the central zone, and 10% to 15% in the transitional zone. If locally invasive, it may spread to the bladder neck, seminal vesicles, and ejaculatory ducts. The mechanism for metastasis to distant parts is still poorly understood. Prostate cancer spreads to the bone early without significant lymph node involvement.

2. Risk Factors

The rates of prostate cancer vary among different populations in the world. This implies the involvement of genetic factors. One good example is the high risk of prostate cancer among those of sub-Saharan African ancestry while the risk becomes lower among the many Asian populations. However, it has been observed that there is an increased risk of prostate cancer among Asians who have migrated to the United States.

This suggests the role of environmental factors such as diet. Prostate cancer is also more likely in those with positive family history. When autopsies are performed in men for other causes of death, prostate cancer is often found. This rate of latent or autopsy cancer is much higher compared to clinical cancer. It is estimated to be as high as 80% by the age of 80 years old. This latent or autopsy rate is found to be similar globally.

3. Genetics

Various studies have identified genetic variants in chromosome 8 in the 8q24 region, which has been associated with the higher risk of prostate cancer. Other genetic alterations include those on the X chromosome (human prostate cancer 1), chromosome 17, and chromosome 1 (hereditary prostate cancer 1 [HPC1] gene and the predisposing for cancer of the prostate [PCAP] gene).

The genetic studies have found that having a strong familial predisposition may be responsible for 5% to 10% of cases. Those with a higher risk may also present 6 to 7 years earlier. Those with BRCA2 mutations tend to have a higher risk of prostate cancer that develops at a younger age and is more aggressive. One study found that germline mutations in HOXB13, a homeobox transcription factor gene, may increase the risk of prostate cancer.

4. Statistics

Globally, the incidence of prostate cancer varies with the highest rates in central Europe, northern Europe, North America, and Australia, while the lowest rates are found in northern Africa, south central Asia, and south eastern Asia. In the United States, it is estimated to occur in 1 in 6 Caucasian men and 1 in 5 African American men; an estimated 175,000 new cases of prostate cancer are expected per year.

Based on a review from about 800,000 cases of prostate cancer between 2004 to 2013, the incidence of low risk prostate cancer was found to have decreased. However, the incidence of metastatic prostate cancer has increased to 72% more than those in 2004. This increase was greatest among men between the ages of 55 to 69 years old. Prostate cancer is most commonly diagnosed among those 65 to 74 years with prevalence rates higher in African American men.

5. Signs and Symptoms

Patients with early stages of prostate cancer have little to no symptoms. Those with symptoms may experience issues similar to those with benign prostatic hyperplasia such as increased urination at night (nocturia), frequent urination, dribbling, difficulty starting urination, painful urination (dysuria), urinary retention, and blood in the urine (hematuria). When prostate cancer is advanced, it can result in symptoms that involve spread or metastasis.

These include weight loss, appetite loss, anemia, pain in the lower extremities, swelling (edema) in the lower limbs due to obstruction of lymphatic and venous vessels, neurological symptoms from compression of the spinal cord, and bone pain (with or without pathological fracture) as prostate cancer tends to metastasize to bone.

6. Investigations

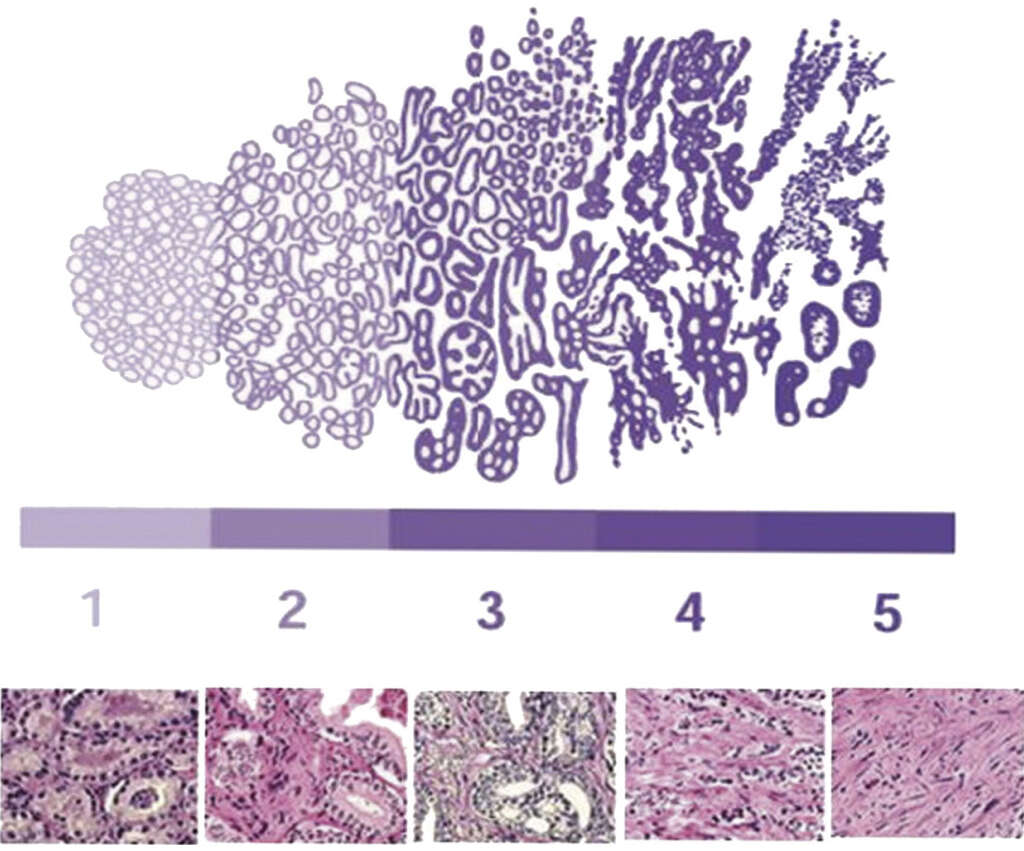

Most cases of prostate cancer are identified through prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening and digital rectal examination (DRE) in asymptomatic men. When the PSA levels are elevated or if DRE findings are abnormal, a needle biopsy of the prostate is recommended. The evaluation from the biopsy is important as it allows the Gleason score to be calculated so prognosis can be determined.

Those with advanced disease may benefit from electrolytes, serum creatinine, and liver function tests. A urinalysis should be performed before cancer therapy is planned. A computed tomography (CT) scan may be helpful for those with a high risk of metastasis to the lymph nodes. Genetic tests for those with a family history of mutations (BRCA 1, BRCA2, and so on) may be recommended.

7. Screening

As previously mentioned, DRE and PSA are commonly used for prostate cancer. A review of 7 studies involving 9,241 patients found that DRE by primary care physicians has poor accuracy for prostate cancer screening. Prostate cancer screening is a controversial issue as screening allows early detection but most cases are low-grade and have little threat of mortality or morbidity.

There are also many clinicians who have also argued that early intervention for prostate cancer does not result in measurable survival advantage. Another review reported that screening for prostate cancer at best leads only to a small reduction in mortality over 10 years. A study analyzing the complications from biopsies and treatment have found that 94 out of 1,000 will have hematospermia and 1 will be hospitalized, most likely for sepsis.

8. Treatment and Management

The treatment and management of prostate cancer depends on the severity, patient preferences, and life expectancy. In prostate cancer that is still localized, the treatments include watchful observation, active surveillance, radiation therapy, radical prostatectomy, and hormone therapy. Other therapies include whole gland cryotherapy, high-intensity focused ultrasound, and proton beam radiation.

In those with locally advanced prostate cancer, radiotherapy with androgen ablation is indicated. In some cases, a radical prostatectomy (surgery) is an option. A combination of hormone therapy, brachytherapy, and external radiation can be used. In metastatic prostate cancer, management is usually palliative to reduce symptoms and slow disease progression. Surgery now includes options where it can be minimally invasive, robotically assisted, nerve sparing, and more. Hormone therapy or androgen deprivation therapy is also an option.

9. Prognosis

The Gleason grade is a tool used to determine the prognosis of prostate cancer based on capsular penetration, margin positivity, and extent of tumor volume. High-grade prostate cancer (Gleason grades 4 and 5) is often associated with poor prognosis due to disease progression and pathologic findings. Low-grade prostate tumors are generally less dangerous.

Based on a review of 11,521 patients who have been treated with radical prostatectomy from 1987 to 2005, the reported mortality rate over 15 years was 7%. The Cancer of the Prostate Risk Assessment (CAPRA) score is also used to predict the prognosis based on the prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels, Gleason score, age at diagnosis, clinical tumor stage, and percentage of biopsy cores that are positive for cancer.

10. Patient Education and Support

Patient education and public awareness is crucial as PSA screening is now easily available. Patient education allows a greater number of men to understand their options regarding screening, diagnosis, staging, and treatment. It allows them to make informed decisions and to select the most appropriate treatment. There is also information and resources available for patients through organizations such as the American Cancer Society, National Cancer Institute, and more.

Patients and family members can also refer to online support groups to help them cope with various issues and learn more about other patient experiences regarding different treatment options. Patients may also benefit from connecting with other patients from their local community.