Impetigo Causes, Symptoms & Treatments

Impetigo is a skin condition that is very common and contagious, as it involves the superficial layer of the skin. While this condition is usually more likely to affect children, it can also occur in adults at any age. In some regions, impetigo is also known as “school sores”. In the year 2010, impetigo affected approximately 2% of the global population (roughly 140 million individuals). Some of the risk factors for impetigo include attendance to daycare, malnutrition, poor hygiene, crowded living situation, contact sports, diabetes, and open wounds in the skin (i.e. insect bites, scabies, herpes, or eczema). Transmission can occur if there is direct contact with lesions of an affected individual, or through fomites (i.e. toys, clothing).

To prevent it from spreading, frequent hand washing and cleaning the affected area can be useful. The condition can be self-limited within a few weeks; however, some cases may require the use of topical and/or systemic antibiotics. Furthermore, some rare complications, such as cellulitis and acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN), can occur.

Cause #1: Staphylococcus Aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is a bacterium that can be found in the human body. It is commonly found in the nose, skin, and respiratory tract. While it is not always pathogenic (it is not always harmful), it can cause many different conditions such as skin infections (i.e. folliculitis, impetigo), food poisoning, respiratory tract infections, bone and joint infections (i.e. osteomyelitis, septic arthritis), and more. Skin infections such as impetigo most frequently occur when there is a wound or disruption of the skin due to trauma, skin infection (i.e. varicella, herpes), or insect bites. The bacteria invade the wound and start colonizing the area causing an infection.

There are two variants of impetigo, known as bullous and non-bullous impetigo. S. aureus can be responsible for either variant; however, when it produces exfoliative toxins (exfoliatins A and B) it will give rise to bullous impetigo. This variant usually occurs on intact skin and can involve mucous membranes (unlike non-bullous impetigo). It consists of small or large superficial lesions called bullae (blisters containing serous fluid) that quickly rupture and spread locally (face, trunk, and upper extremities) through autoinoculation. Finally, there are resistant strains of the bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA), that can present with different cutaneous manifestations (i.e. abscesses).

Cause #2: Streptococcus Pyogenes

Streptococcus pyogenes is a round bacterium (cocci) that is Gram positive (retains the color of a special stain). It is part of a group of bacteria known as the group A streptococcus (GAS). It is also found in the nose and throat of some of the general population. As the name suggests, infections caused by this bacterium often form pus.

Like staphylococcus aureus, streptococcus pyogenes also takes advantage of breaks in the skin to invade and colonize the skin. S. pyogenes only causes the nonbullous variant, and remains the most common cause of nonbullous impetigo. This variant is the most contagious. Patients initially report a single red and inflamed lesion on the skin that rapidly evolves into a vesicle or pustule that ruptures. Finally, the released contents of the lesion dry and form a honey- colored exudate that ends up covering the erosion. Nonbullous impetigo spreads rapidly to contiguous areas or, through scratching, to distal areas (mostly face and extremities). Patients can also report inflammation of regional lymph nodes.

Cause #3: Risk Factors

Besides staphylococcus aureus and streptococcus pyogenes being the main cause of impetigo, there are also several other factors that contribute to the infection of the skin. They are highlighted as a cause for impetigo as they affect the growth of the bacteria. Without these factors, the infection might not even occur.

One of the biggest factors is poor hygiene as it helps the spread of bacteria. Being in a crowded area for various reasons such as work, school, or living situation also promotes the spread of infection. Increased contact through sports is also a contributing factor. If you are living in an area with hot and humid weather, both bacteria thrive in these conditions. Finally, immunosuppression (i.e. medications), systemic diseases (i.e. diabetes mellitus), and intravenous drug abuse can also encourage bacterial growth.

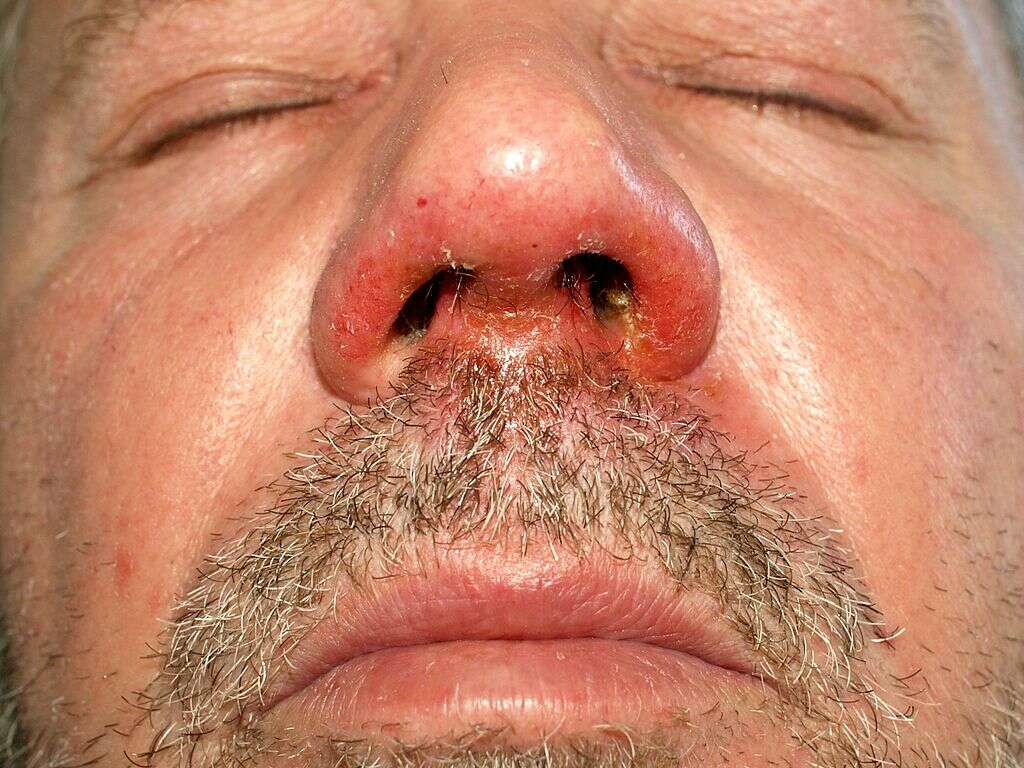

Symptom #1: Skin lesions

Patients with nonbullous impetigo begin with a single red lesion on the skin that turns into a vesicle or pustule that ruptures and releases its contents. Thus, a dry, honey-colored exudate ends up covering the erosion forming a crust. These lesions can spread, and mostly affect the face and extremities.

Patients with bullous impetigo report small or large superficial lesions called bullae (blisters containing serous fluid) that quickly rupture and spread locally (face, trunk, and upper extremities) through autoinoculation (i.e. scratching). Since these lesions are fragile they can rupture quickly and only their remnants (collarettes) may be seen at presentation.

Symptom #2: Associated Symptoms

The blisters that occur can be itchy and painful. It is important to try not to scratch at it as it can cause the infection to spread. Patient awareness is important to prevent the infection from spreading to other parts of the body. Handwashing is key as the infection spreads through fingers, clothing, and towels. In infants with bullous impetigo, systemic symptoms such as fever, diarrhea, or generalized weakness can be present.

Depending on the areas that are affected and the condition of sores, the lymph nodes that are draining the affected area can be swollen (mostly in nonbullous impetigo). Individuals with impetigo are advised to stay at home to prevent the spreading of infection.

Symptom #3: Ecthyma

Ecthyma is a deeper and more severe form of impetigo where there are deeper erosions into the layers of the skin. Untreated impetigo or impetigo in patients with poor hygiene can become ecthyma. It most commonly affects areas such as thighs, legs, buttocks, feet, and ankles. It has all the same risk factors as impetigo. In patients with ecthyma, the removal of the crust (usually thicker than in impetigo) will reveal an indurated ulcer with raised margins.

These lesions can resolve without treatment, stay fixed in size, or can worsen and enlarge to become sores that are 0.5 to 3 centimeters in diameter. Thus, these lesions commonly leave a scar. Ecthyma can cause invasive complications such as cellulitis, lymphangitis, erysipelas, gangrene, permanent scarring, and rarely, post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (involvement of the kidneys).

Treatment #1: Topical Antibiotics

Some patients with impetigo may require treatment with a topical antibiotic alone, while others can require a combination of systemic and topical agents. Importantly, the agents chosen must cover both Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes.

Topical agents are used for small areas of involvement or single lesions of nonbullous impetigo. Topical agents have the advantage of no systemic adverse effects and decreasing antibiotic resistance.

Treatment #2: Wound care

In the treatment of localized, uncomplicated impetigo topical wound cleansing is indicated. Local wound care along with antibiotic therapy can be prescribed for the treatment of impetigo.

For nonbullous impetigo, your doctor may recommend gentle cleansing of the lesions with antibacterial soap and removal of the crusts, along with the application of wet dressings on the lesions. These steps should be repeated regularly until the area starts to heal. Ensure that the area is properly dried and if topical antibiotics were prescribed apply as directed.

Treatment #3: Systemic Antibiotics

Systemic antibiotics are usually reserved for generalized impetigo, complicated infections, patients with associated manifestations (i.e. post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis), or for cases where topical therapy is not practical. Thus, systemic agents are frequently prescribed in nonbullous impetigo (extensive involvement of the skin) and bullous impetigo.

Furthermore, your doctor may choose to combine both topical and systemic therapies for treatment. Finally, systemic antibiotics can also be recommended if there are multiple cases of impetigo among family members; as well as in daycare or athletic team settings.